Iconography

Crafting Sacred Art that Connects the Earthly and Divine

What is Iconography

Iconography is the sacred art of creating religious images, known as icons, that depict Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical scenes.

These images are more than artistic representations; they serve as windows to the divine, guiding worshippers in prayer and spiritual reflection. The making of icons follows a meticulous and symbolic process rooted in tradition. Artists, often referred to as iconographers, begin by preparing a wooden panel with layers of gesso to create a smooth surface. Using natural pigments mixed with egg tempera, they carefully paint the image, layer by layer, following established theological and artistic guidelines. Gold leaf is often applied to halos and backgrounds, symbolizing divine light. Each step is undertaken with prayer and intention, imbuing the icon with spiritual significance and connecting the artist to a centuries-old tradition.

History and Contemporary Relevance of Iconography

The timeless appeal of illuminated manuscripts continues to influence modern art and design. Gold leaf, intricate patterns, and vibrant colors now enrich a variety of creative works, bridging history and innovation.

Historical Background

Iconography, the art of creating sacred images, has been a cornerstone of religious and cultural expression for centuries. Rooted in the traditions of the Byzantine Empire, iconography gained prominence as a visual language for conveying spiritual truths and divine presence. Icons, often depicting Christ, the Virgin Mary, saints, and biblical scenes, served as devotional tools, mediating the connection between the earthly and the divine.

The creation of icons followed strict theological and artistic guidelines, with each element imbued with symbolic meaning. From the golden halos signifying holiness to the serene expressions of the figures, every detail reflected spiritual ideals. Iconography flourished across Orthodox Christian regions, influencing art in Eastern Europe, Russia, and beyond.

Contemporary Relevance

Today, iconography remains a vibrant tradition. It continues to play a central role in liturgical practices and spiritual devotion within Orthodox Christianity. Beyond its religious significance, contemporary artists and art enthusiasts embrace iconography as a medium for exploring themes of spirituality, cultural heritage, and timeless beauty.

The techniques and principles of traditional iconography are also being adapted for modern applications, such as murals, digital illustrations, and interfaith artistic expressions. This blend of historical methods and contemporary creativity ensures the enduring relevance of the art form.

Materials Required for Iconography

- Surface Preparation

- Wooden Panels: Traditionally prepared with layers of gesso for a smooth, durable surface.

- Canvas: Occasionally used for large-scale icons or portable works.

- Pigments and Paint

- Egg Tempera: A classic medium made by mixing ground pigments with egg yolk and water.

- Natural Pigments: Derived from minerals, plants, or other natural sources, ensuring vibrant and durable colors.

- Gesso and Clay Bole

- Gesso - Whiting: The gesso layer in iconography is a smooth, white ground made of chalk or gypsum mixed with glue, applied to wooden panels to create a stable and absorbent surface for painting and gilding.

- Burnishing Clays: Pigmented clay bole is typically a reddish or yellowish clay mixed with animal glue, applied beneath gold leaf to enhance its brilliance and provide a smooth surface for burnishing.

- Adhesives (Size)

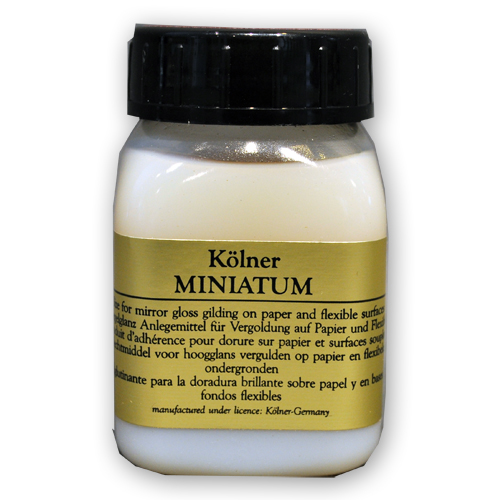

- Gilding Size: Includes traditional glair (egg white), gelatin-based options and unique products like Instacoll, Miniatum and Miniatum Ink.

- Gold Leaf

- Loose Gold Leaf: Traditional, delicate sheets of pure gold.

- Shell Gold: Gold powder blended with Gum Arabic

- Imitation Gold Leaf: Affordable for practice.

- Brushes

- Fine Sable Brushes: For detailed work and smooth lines.

- Gilder's Tip Brushes: Gilder's Tip brushes are for picking up loose gold leaf from a gilders pad or direct from the booklet and transferring to the object being gilded.

- Soft Gilding Brushes: For applying and burnishing gold leaf.

- Tools for Gilding

- Gilding Knife: For cutting gold leaf.

- Gilding Pad or Cushion: A padded surface for handling gold leaf.

- Cotton Gloves: To avoid fingerprints on delicate gold leaf.

- Tools for Burnishing

- Burnishing Tools: Agate or hematite-tipped tools for polishing gold.

- Tools for Drawing and Designing

- Charcoal or Graphite Pencils: For preliminary sketches and transferring designs.

- Templates and Compasses: For creating geometric patterns and proportional figures.

- Protective Finishes

- Olifa (Linseed Oil Varnish): Traditionally used to seal and protect icons.

- Modern Varnishes: Clear acrylic or resin-based finishes for durability.

- Other Essentials

- Palette and Mixing Tray: For preparing pigments and tempera.

- Distilled Water: To mix with pigments and clean brushes.

- Cotton Cloths: For cleaning and polishing/li>

- Work Light: To ensure even illumination during detailed work.

Optional Enhancements

- Silver Leaf: For variation and contrast.

- Shell Gold: Pre-ground gold for fine details.

- Antiquing Glazes: To create an aged effect.

Historic Highlights of the Art of Iconography

Iconography, as a sacred art form, has a rich history deeply rooted in religious and cultural traditions. Over centuries, it has evolved, reflecting theological, artistic, and societal influences. Here are some of its historic highlights:

1. Early Christian Origins (3rd–6th Century)

Iconography emerged in the early Christian communities of the Roman Empire, using visual symbols like the fish (Ichthys) and the Chi-Rho to express faith during periods of persecution.

The first icons were simple and symbolic, often found in catacombs and early Christian basilicas.

2. The Byzantine Golden Age (6th–15th Century)

The Byzantine Empire is considered the cradle of classical iconography, where the art form flourished.

Icons became central to Orthodox Christian worship, revered as "windows to heaven."

Famous examples include:

The Christ Pantocrator of Sinai (6th century): One of the earliest surviving Byzantine icons, housed in St. Catherine's Monastery.

The Virgin Hodegetria: Depictions of the Virgin Mary pointing to Christ as the "way" became a widely revered motif.

The period also saw the codification of iconographic conventions, ensuring theological accuracy and stylistic consistency.

3. The Iconoclastic Controversy (8th–9th Century)

A pivotal moment in iconographic history was the Iconoclastic Controversy, during which the use of religious images was debated.

Icons were destroyed during this period by iconoclasts who viewed them as idolatrous.

The eventual triumph of the iconophiles (icon supporters) in 843 CE, marked by the Feast of Orthodoxy, reaffirmed the centrality of icons in worship.

4. Russian Iconography (12th–17th Century)

Russia adopted Byzantine traditions after its conversion to Christianity in 988 CE, developing its unique iconographic style.

Andrei Rublev (1360–1430): A master iconographer whose Trinity Icon is celebrated for its spiritual depth and harmony.

Russian icons often featured intricate gold backgrounds and vibrant color palettes, embodying a sense of divine transcendence.

5. The Renaissance and Baroque Influence (15th–17th Century)

In Western Europe, Renaissance and Baroque art diverged from the strict conventions of Byzantine iconography.

Icons in Catholic contexts became more naturalistic, with increased emphasis on emotional expression and dynamic compositions.

The Counter-Reformation also encouraged the creation of religious art that could inspire devotion and reaffirm Catholic doctrine.

6. Revival in the Modern Era (19th–21st Century)

The 19th and 20th centuries saw a revival of interest in traditional iconography, particularly in Orthodox Christian communities.

Artists and theologians revisited ancient techniques, re-establishing the importance of icons as sacred art.

Modern iconographers like Leonid Ouspensky and Georges Rouault have combined traditional methods with contemporary sensibilities.

Significance

The historic highlights of iconography demonstrate its enduring role as a bridge between the earthly and the divine. From Byzantine churches to contemporary studios, icons continue to inspire reverence, connecting believers to centuries of spiritual and artistic tradition.